Today’s artists express their vision by stretching far beyond the boundaries of canvas and paint. Through unorthodox juxtapositions of light, color, video, sound, and nature, artists such as Bill Fontana and the artist couple Christo and Jeanne-Claude create immersive experiences that require the input of a complex and highly adaptable network of collaborators—including the spectators themselves, each of whom comes away with a highly personalized experience. To succeed, this type of ambitious endeavor requires radical connectivity, an open mind, and a wide range of players. The collaboration itself and the interplay of different elements create artistic value.

The same is true for the complex ecosystems now emerging throughout the business landscape and across industries—and for the new ways they deliver value. As the Internet of Things (IoT) makes our homes, phones, and cars “smart,” companies must work with a far wider range of partners to pull together the underlying technologies, applications, software platforms, and services needed for an integrated solution. The need for partnerships is further amplified by rapidly changing technologies and consumers’ growing demand for a highly customized user experience.

Today’s “smart” products depend on complex networks of partners. But few companies know how to manage these networks effectively.

Some large networks, such as the digital ecosystems of smartphones, comprise a million or more platform partnerships through their integrated app stores. And it’s not just the tech industry that’s undergoing these changes. All industries—including incumbents such as banking, health care, consumer products, logistics, and automotive—are seeing an evolution of their products and services and a need to collaborate differently.

This new reality can be especially challenging for incumbent players, many of which are used to going it alone—either by trying out new things in-house or by buying a company in order to enter a new space. And when they do set up partnerships or make acquisitions, they often end up with an ecosystem more by accident than by virtue of long-term strategic planning.

A better approach is to actively participate in shaping the new landscape. To this end, many leading companies are building their own collaborative networks and/or joining existing ones. The challenge is how to effectively set up and manage these ecosystems and use them strategically to maximize value—and gain a competitive edge. Companies that can meet this challenge will reap enormous benefits, while those that don’t risk falling behind or becoming irrelevant.

In this article we’ll explore a number of key strategic questions, including:

- How collaboration within an ecosystem is different from traditional collaboration

- What types of ecosystems are available and which are best suited for incumbents

- How incumbents can gain a competitive advantage through the strategic use of digital ecosystems

The New Collaboration Model

Just as contemporary art installations are completely unlike traditional paintings, the members of today’s digital ecosystems collaborate in ways that are fundamentally different from collaborations of the past. Case in point: the auto industry, which is currently undergoing radical changes. In the past, automakers either formed a joint venture or alliance with an OEM to enter a new market (such as China) or formed contractual relationships with hundreds of suppliers to secure parts. These traditional partnerships still exist, but today a typical European auto company will draw on an ecosystem of more than 30 partners across five different industries and several countries to make cars that are connected, electric, and autonomous. (See Exhibit 1.) The auto company acts as the “orchestrator,” whose role is to organize and manage the ecosystem, define the strategy, and identify potential participants.

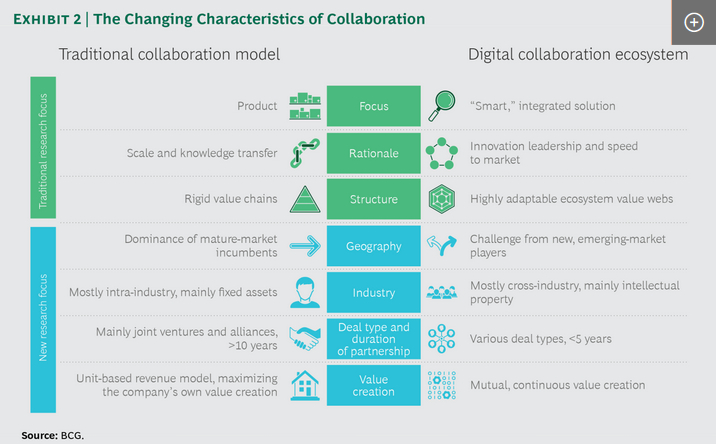

Today’s collaborations have a different purpose, structure, and outcome than those of the past—and industry lines are becoming increasingly blurred. Articles in academic and business journals have explored only limited aspects of these differences, such as the new focus on smart, integrated solutions;1 the goal of achieving innovation leadership and speed to market;2 and the shift from rigid value chains to highly adaptable value webs.3 But these are only part of the story.

Our extensive research into 40 ecosystems revealed four additional aspects of the new digital ecosystems that are changing how companies collaborate: geographic diversity of participants; cross-industry focus; shorter, more flexible deal structures; and mutual, continuous value creation. (See Exhibit 2.)

…

Super Platforms: Integrating Several Platforms into One Fully Integrated Offering

Some platforms integrate a wide range of complementary platforms into a single, fully integrated super platform. A good example is a digital assistant that integrates transportation, payment, shopping, and communication services into a single user-friendly solution. This type of ecosystem requires advanced digital capabilities, an openness to outside partners, and a well-established platform to start with. For these reasons, it tends to be preferred by well-established tech companies.

Number and Type of Partners. This type of ecosystem depends on a high volume of users driven by a limited number of well-established partner platforms and their contributors, which number in the millions. As a result, super platforms are open—even to competitors, if they can add unique features. For instance, Amazon’s Alexa integrated the Sonos smart-speaker platform to attract high-end users. Rather than standardizing partner screening, super platforms focus on strategic considerations, such as what impact potential partners will have on the overall market opportunity, product cannibalization, and user lock-in.

Role of Orchestrator. Since super platforms have a relatively small number of partners (i.e., the partner platforms), the orchestrator can focus on negotiating the strategic aspects of the ecosystem, such as data sharing, exclusivity, and any changes to the platform that affect services or functionality. The orchestrator’s negotiating strength depends on the power of the super platform, which is a direct function of the number of engaged users and the products and services that are already integrated. The orchestrator also sets technical requirements for the partner platforms.

Another key focus is on providing a best-in-class customer interface and user experience to drive user engagement, grow the user base, and attract other partner platforms. Both Amazon Alexa and WeChat, two well-established super platforms, offer highly intuitive user interfaces that draw upon extensive user preference data from the companies’ other businesses. The two super platforms also integrated their own adjacent services and platforms before adding key partners. This allowed them to experiment with integration, prove the viability of the combined offering, and build up their user base—all of which made the platforms more attractive to potential partners.

A strong financial backbone is needed to grow a super platform. For instance, Amazon launched an extensive marketing campaign to promote Alexa and discounted speaker prices to bring in users. It also provides financial support (via the Alexa Fund) and gives programmers financial incentives to develop skills that continually increase Alexa’s usability and appeal.

Value Creation. A super platform makes money largely through adjacent, mostly data-based businesses, such as ads, e-commerce payments, and new service offerings. A good example is WeChat, which started as a social messenger and now allows users to buy and sell products, send money to friends, order food and groceries, and check news. Customizing service offerings and building adjacent businesses that users want and need require a broad set of user data. Super platforms therefore focus partner negotiations on trying to safeguard their own data and get access to the data of other integrated platforms.

Key Success Factors. Our research suggests that a successful super platform needs a well-established technology foundation, a superior user interface and experience, and strong financial backing.

Looking Ahead

Companies used to work primarily one to one with another companies, but that was ten years ago. To create products today, Niki Lang says that companies need to have an array of partners.

In today’s connected world, industry and geographic boundaries are becoming meaningless, and unexpected change has become a constant. Adaptable ecosystems are designed to respond more quickly to evolving demand patterns, customer preferences, and the competitive landscape.

The new art of setting up and managing these broad collaborative networks—and leveraging their potential—is still uncharted territory for most businesses. The insights described above provide a starting point. Forward-looking companies that can capitalize on the potential power of ecosystems will reap enormous benefits and be well positioned for an uncertain future.

Nikolaus Lang Managing Director & Senior Partner; Global Leader, Global Advantage Practice, Munich;

Konrad von Szczepanski Managing Director & Partner, London

Charline Wurzer Project Leader, Munich

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.