As cybersecurity threats compound the risks of financial crime and fraud, institutions are crossing functional boundaries to enable collaborative resistance.

In 2018, the World Economic Forum noted that fraud and financial crime was a trillion-dollar industry, reporting that private companies spent approximately $8.2 billion on anti–money laundering (AML) controls alone in 2017. The crimes themselves, detected and undetected, have become more numerous and costly than ever. In a widely cited estimate, for every dollar of fraud institutions lose nearly three dollars, once associated costs are added to the fraud loss itself. 1 Risks for banks arise from diverse factors, including vulnerabilities to fraud and financial crime inherent in automation and digitization, massive growth in transaction volumes, and the greater integration of financial systems within countries and internationally. Cybercrime and malicious hacking have also intensified. In the domain of financial crime, meanwhile, regulators continually revise rules, increasingly to account for illegal trafficking and money laundering, and governments have ratcheted up the use of economic sanctions, targeting countries, public and private entities, and even individuals. Institutions are finding that their existing approaches to fighting such crimes cannot satisfactorily handle the many threats and burdens. For this reason, leaders are transforming their operating models to obtain a holistic view of the evolving landscape of financial crime. This view becomes the starting point of efficient and effective management of fraud risk.

The evolution of fraud and financial crime

Fraud and financial crime adapt to developments in the domains they plunder. (Most financial institutions draw a distinction between these two types of crimes: for a view on the distinction, or lack thereof, see the sidebar “Financial crime or fraud?”) With the advent of digitization and automation of financial systems, these crimes have become more electronically sophisticated and impersonal.

Financial crime or fraud?

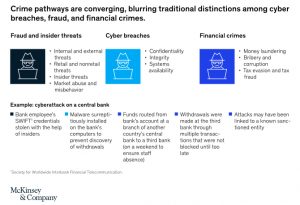

For purposes of detection, interdiction, and prevention, many institutions draw a distinction between fraud and financial crime. Boundaries are blurring, especially since the rise of cyberthreats, which reveal the extent to which criminal activities have become more complex and interrelated. What’s more, the distinction is not based on law, and regulators sometimes view it as the result of organizational silos. Nevertheless, financial crime has generally meant money laundering and a few other criminal transgressions, including bribery and tax evasion, involving the use of financial services in support of criminal enterprises. It is most often addressed as a compliance issue, as when financial institutions avert fines with anti–money laundering activities. Fraud, on the other hand, generally designates a host of crimes, such as forgery, credit scams, and insider threats, involving deception of financial personnel or services to commit theft. Financial institutions have generally approached fraud as a loss problem, lately applying advanced analytics for detection and even real-time interdiction. As the distinction between these three categories of crime have become less relevant, financial institutions need to use many of the same tools to protect assets against all of them.

One series of crimes, the so-called Carbanak attacks beginning in 2013, well illustrates the cyber profile of much of present-day financial crime and fraud. These were malware-based bank thefts totaling more than $1 billion. The attackers, an organized criminal gang, gained access to systems through phishing and then transferred fraudulently inflated balances to their own accounts or programmed ATMs to dispense cash to waiting accomplices (Exhibit 1).

We strive to provide individuals with disabilities equal access to our website. If you would like information about this content we will be happy to work with you. Please email us at: McKinsey_Website_Accessibility@mckinsey.com

Significantly, this crime was one simultaneous, coordinated attack against many banks. The attackers exhibited a sophisticated knowledge of the cyber environment and likely understood banking processes, controls, and even vulnerabilities arising from siloed organizations and governance. They also made use of several channels, including ATMs, credit and debit cards, and wire transfers. The attacks revealed that meaningful distinctions among cyberattacks, fraud, and financial crime are disappearing. Banks have not yet addressed these new intersections, which transgress the boundary lines most have erected between the types of crimes (Exhibit 2).

More: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk

Authors: Salim Hasham is a partner in McKinsey’s New York office, where Shoan Joshi is a senior expert; Daniel Mikkelsen is a senior partner in the London office.