Thinking about purpose in business was once a provocative and urgent activity. A seminal HBR article from 1994 states, “In most corporations today, people no longer know—or even care—what or why their companies are,” and argues that “strategies can engender strong, enduring emotional attachments only when they are embedded in a broader organizational purpose.” At the time, purpose was a disruptive idea, reminding companies how disconnected they had become from their raison d’être and inspiring them to re-articulate it, recommit to it, and mobilize around it.

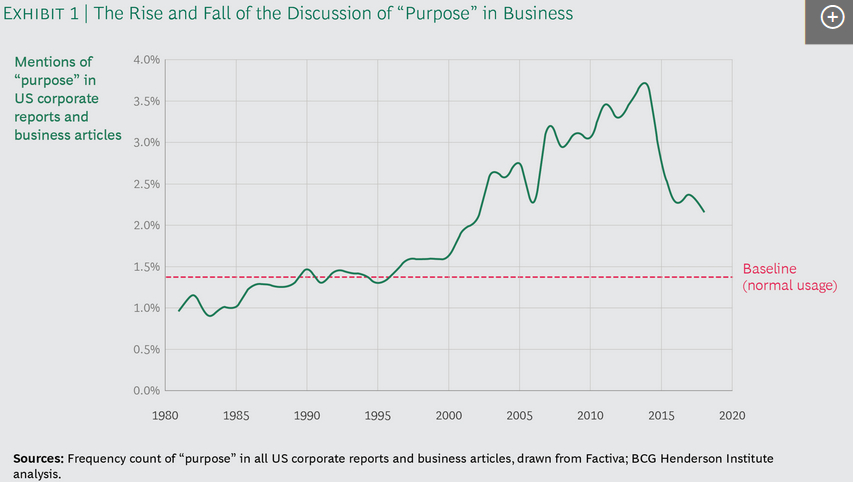

Yet like many new ideas in business, what starts out as a provocation can easily become an empty word, a comfortable routine, or even an excuse for not facing the toughest issues. Indeed, interest in purpose has surged, peaked, and declined, suggesting that the concept, like CSR, agile, and other initially powerful business ideas, has been overused and diluted. (See Exhibit 1.)

A clear sign that purpose has lost its power is if discussing it is easy and comfortable—if in articulating purpose you are merely describing, rather than disrupting, how your company works. Such discussions are probably not adding much value. Yet the reasons for a serious consideration of purpose have only become more urgent. How can we get back to the raw power of the idea of purpose and jettison the ambiguity, complacency, and ritualization that have grown up around it?

What Is Purpose?

Purpose is developed at the intersection of aspiration, external need, and action. A purpose is an enduring aspiration formed around a need in the world that a company is willing and able to act on, using either intrinsic strengths or capabilities it could develop. For example, the world’s oldest company, Japanese construction firm Kongō Gumi, describes its purpose this way: “Kongō Gumi constructs shrines and temples that cultivate and bring calmness to your mind.”1 Although the company has probably articulated this purpose in different ways over time, and its offering and operations have evolved (the company was recently acquired), it has pursued the core social good of bringing calm to people’s minds since its founding 1,440 years ago.

At the heart of the idea of purpose are a number of discomforting tensions. (See Exhibit 2.) There is the tension between idealism and realism: on the one hand, you want to set forth an ideal that pushes your company to become something greater than it currently is, but on the other hand, you don’t want videos and speeches articulating lofty aspirations that are grossly mismatched with your company’s intention and capability to act. Reality without ideals takes you nowhere, but ideals without reality are equally fruitless: you end up either ignoring the ideal or pretending you are already living it.

Then there is the tension between imagination and existing needs. One can be guided by a dream—of what people’s lives or society could be like—using it as the basis for articulating a new need. Or one can set out to meet a palpable existing need. Serving acknowledged needs is likely to be more realistic but also to provide less differentiation from others. Shaping new needs offers greater possibilities for uniqueness and profit but is likely to be less feasible.

There is also the tension between having a positive impact on society and maintaining financial viability. When addressing an ideal cannot generate a return, the purpose will not be sustainable. On the other hand, when the need is conceived as little more than providing a useful product, the purpose is hardly inspiring. The tension is between fulfilling a societal need and keeping the machine of the business running to fund the purpose on a sustainable basis.

Finally, there is the tension between consistency of purpose over time and adaptation to changing conditions. On the one hand, a commitment that can be broken and reframed too easily is not a principled basis for an enduring identity. On the other, aspirations, needs, and capabilities all change over time, indicated by the dotted triangle in Exhibit 2; it is natural that even if your purpose endures, how you understand and act on it evolves as you experiment and learn in a changing world.

A good purpose integrates and balances all of these tensions. It is a balance of idealism (setting a real aspiration) and realism (not ignoring brutal truths); it is an imaginative way to meet a genuine need; it suggests a path for making an impact while attracting and maintaining sufficient resources to do so; and it captures what is timeless while leaving room for evolution of thought and action.

By Ashley Grice , Martin Reeves , and Jack Fuller

More: The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.