The private sector plays an essential role in humanitarian preparedness, response, and recovery efforts, but large numbers of independent actors—no matter how well intentioned—can introduce complexity and potential duplication of efforts, particularly when companies react in an ad hoc or uncoordinated way.

To deliver maximum impact, many forward-thinking companies have begun to forge private-sector networks. These networks of companies and local businesses collaborate in a country or region to strengthen their own risk preparedness and to mobilize and coordinate the private-sector response to an emergency.

In the lead-up to the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit (WHS), the United Nations consulted with more than 900 stakeholders (including large global companies as well as small and medium-sized enterprises) to try to understand how the private sector could best contribute to disaster risk reduction, preparedness, response, and recovery. As a result, the WHS called on the private sector to join with governments and other humanitarian actors in addressing the growing humanitarian challenges facing societies.

By participating in these networks, companies can better identify their own vulnerabilities to hazards, improve their ability to reduce and manage risk and protect their workforce, understand how they can contribute to their communities in times of emergency, and develop new mechanisms and processes that allow them to recover more quickly in the wake of a crisis. It’s a smart move from a business perspective—and networks provide extraordinary benefits for society as well. When companies engage directly with key humanitarian actors in a coordinated way, they can deploy their unique capabilities and resources where they are needed most, which is enormously beneficial to communities in crisis.

A World of Hazards

Private-sector networks address three types of hazards.

- Natural Hazards. These are natural processes or phenomena—such as earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, droughts, volcanic activity, and landslides—that may cause injury or loss of life, property damage, social or economic disruption, or environmental degradation.

- Health Epidemics. These occur when a disease becomes widespread, clearly in excess of expected levels in a certain location and for a specific period. Recent examples include instances when Ebola, H1N1, and Zika led to epidemics.

- Man-Made Hazards. Examples include food shortages, industrial accidents, and conflict. They may involve political complexities, making it more challenging for the private sector to respond.

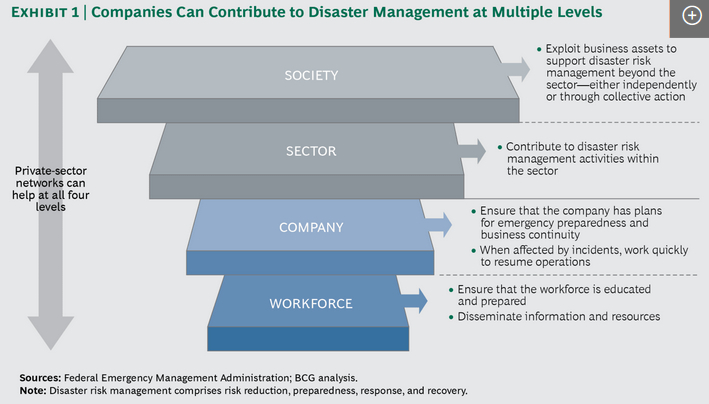

For companies to make a difference when disaster strikes, they must be well prepared at four levels. (See Exhibit 1.) At its foundation, a resilient company requires a prepared and ready workforce, and therefore companies must prepare employees for emergencies and help protect them and their families from harm. Employees must have adequate training and access to resources in order to respond safely and effectively in an emergency.

Given a prepared and ready workforce, the company then needs strong business-continuity planning and smart, well-understood processes to secure company assets and keep operations running with minimal downtime when disaster strikes.

The better prepared companies are in an industry sector, the better the sector will be positioned to respond in an emergency and the more valuable it will become as a partner to government and society in meeting the challenges of disasters and recovery. Furthermore, when companies in, for example, energy, communications, logistics, health, infrastructure, and consumer goods come back online quickly, the total economic and social impact of a disaster is smaller.

In addition, companies can contribute beyond their own sector at the societal level to support operations nationally, regionally, or even globally. For example, logistics companies may transport emergency supplies to affected areas, or telecommunications companies may exploit their communications network to send emergency messages. (See “Lessons from Fiji.”)

By Wendy Woods , David Young , Rudolf Müller , Marcos Neto , and Marcy Vigoda

More: https://www.bcg.com/publications/