McK What matters most Five priorities for CEOs in the next normal

What matters most? Five priorities for CEOs in the next normal

Download this collection of insights on the five priorities global executives have told us they’re focusing on as they navigate the trends shaping the future.

Over the course of the pandemic, businesses have largely—and often successfully—adapted to new ways of working. They’ve also embraced digitization and reorganized their supply chains. All of this has been necessary, but it will not be enough. To prepare for the post-COVID-19 era, leaders need to do more than fine-tune their day-to-day tasks; they need to be ready and willing to rethink how they operate, and even why they exist. To put it another way, leaders need to step back, take a breath, and consider a broader perspective.

The pandemic has both revealed and accelerated a number of trends that will play a substantial role in the shape of the future global economy. In our conversations with global executives, they have identified five priorities. Companies will want to adopt these five priorities as their North Star while they navigate the trends that are molding the future. (Click on the tiles of the interactive below for more on each priority, including links to relevant articles.)

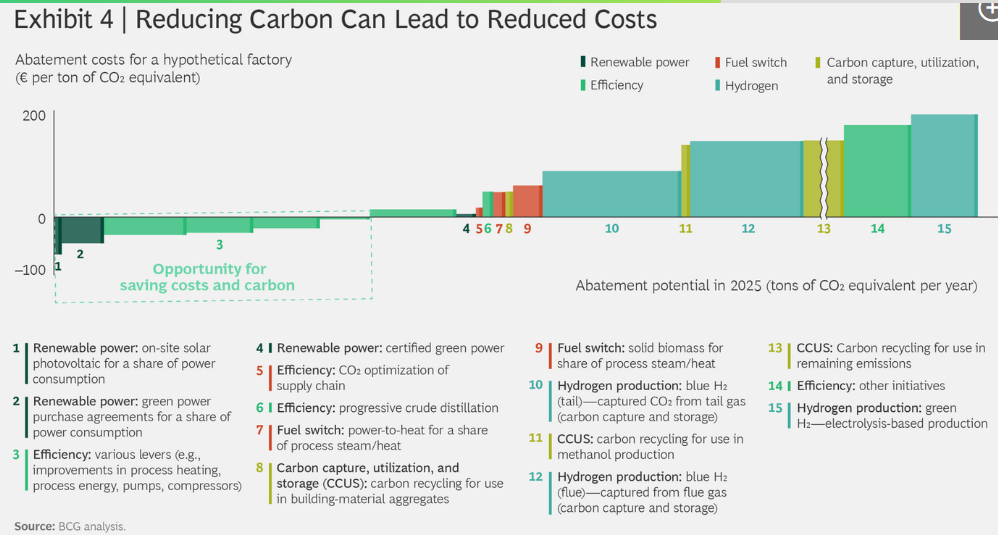

Take sustainability, the principle of producing goods and services while exacting minimal damage to the environment. Many companies have taken earnest steps in this regard because they wanted to. In the very near future, however, doing so will be as fundamental to doing business as compiling a balance sheet: consumers and regulators will insist on it. In this context, sustainability needs to be done as systematically as digitization or strategy development because it will be an important source of long-term competitive advantage.

Click each card to learn more: McKinsey.com/thenextnormal.

Center strategy on sustainability

Center strategy on sustainability. Business can act to ensure that sustainability is more than a buzzword. One possibility is to consider investing in technologies that suck carbon from the atmosphere. Make no mistake: given current and future commitments, climate is going to be an increasingly important way to create competitive advantage.

Organizing for sustainability success: Where, and how, leaders can startHow negative emissions can help organizations meet their climate goalsWhy investing in nature is key to climate mitigation

Transform in the cloud

Transform in the cloud. The cloud’s potential to create value has long been clear—but now its capabilities are becoming grounded in reality. By enabling both speed and scale, the cloud is critical to innovation. By 2030, there could be $1 trillion at stake—and it’s likely that early adopters will win the lion’s share.

Three actions CEOs can take to get value from cloud computingCloud’s trillion-dollar prize is up for grabs

Cultivate your talent

Cultivate your talent. Talent is the most important natural resource, and leading companies are showing how to develop it. They coach and empower small teams; deploy talent based on skills, not hierarchy; and fill gaps through training and development. The bottom line: a better employee experience delivers better results.

The new possible: How HR can help build the organization of the futureTackling Asia’s talent challenge: How to adapt to a digital futureThe new science of talent: From roles to returns

Press the need for speed

Press the need for speed. The pandemic forced many organizations to move fast. Now the priority is to sustain that speed by designing it into the organization. Think of speed as a muscle to be developed. Invest in new collaboration technologies. Anticipate shifts in demand. Focus on outcomes.

Speed and resilience: Five priorities for the next five monthsReturn as a muscle: How lessons from COVID-19 can shape a robust operating model for hybrid and beyondOrganizing for speed in advanced industries

Operate with purpose

Operate with purpose. Employees want to work at places that have a sense of purpose—and will leave if they don’t find it. Companies that execute with purpose are more likely to generate long-term value. And people expect business to do more than make money for shareholders—although that is essential.

The case for stakeholder capitalismHelp your employees find purpose—or watch them leaveMore than a mission statement: How the 5Ps embed purpose to deliver value

Or consider the cloud. Its potential has long been recognized; now it is beginning to bring real results in innovation and productivity. A second priority, then, is for companies to deploy the cloud for good purpose. To do so, their people need to be “cloud literate”—that is, to have a keen sense of the cloud’s capabilities.

As ever, it’s the human element that makes the difference. Developing talent is therefore another priority. The organization of the future will not—or, at least, should not—look like the one that existed as recently as 2019. It will need to be more flexible, less hierarchical, and more diverse.

And faster. The pace of change is speeding up, and the landscape of business is more fluid than ever. The need for speed—a fourth priority—is therefore acute. But this speed needs to be sustainable. Businesses did remarkable things in the early months of the pandemic, fueled by adrenaline and a sense of urgency. In the future, speed needs to be embedded into the organization. To put it another way, speed is not just about revving the engine faster, but designing it to run more efficiently and intelligently.

Finally, leaders need to recognize that people want meaning in their lives, and their work. Previous research has found that companies with a strong sense of purpose outperform those that lack one. And those who say they live their purpose at work are simply better employees—more loyal, more likely to go the extra mile, and less likely to leave. Purpose helps companies recognize emerging opportunities and connect with their customers. This, too, should therefore be seen as a priority and a source of competitive advantage.

How these five priorities are implemented will vary from company to company; some will be more important than others, depending on the market. But we believe—and executives around the world with whom we have worked agree—that mastering these five priorities will substantially improve the odds of success.

The articles listed in the interactive can be downloaded here. Our entire collection of individual insights related to the next normal is at McKinsey.com/thenextnormal.

About the authors

Homayoun Hatami; Global Leader, Capabilities Practices, Paris; LinkedIn; Email

Liz Hilton Segel; Global Leader, Industry Practices, New York; LinkedIn; Email