The Boston Consulting Group’s Strategy Institute is taking a fresh look at some of BCG’s classic thinking on strategy to explore its relevance to today’s business environment. This article, the fourth in the series, examines the growth share matrix, a portfolio management tool developed by BCG founder Bruce Henderson. More than 40 years after Bruce Henderson proposed BCG’s growth-share matrix, the concept is very much alive. Companies continue to need a method to manage their portfolio of products, R&D investments, and business units in a disciplined and systematic way. Harvard Business Review recently named it one of the frameworks that changed the world. The matrix is central in business school teaching on strategy.

At the same time, the world has changed in ways that have a fundamental impact on the original intent of the matrix: since 1970, when it was introduced, conglomerates have become less prevalent, change has accelerated, and competitive advantage has become less durable. Given all that, is the BCG growth-share matrix still relevant? Yes, but with some important enhancements.

The Original Matrix

“A company should have a portfolio of products with different growth rates and different market shares. The portfolio composition is a function of the balance between cash flows.… Margins and cash generated are a function of market share.”

—Bruce Henderson,

“The Product Portfolio,” 1970

…

BCG Matrix 2.0 in Practice

To get the most out of the matrix for successful experimentation in the modern business environment, companies need to focus on four practical imperatives:

Accelerate. It is critical to evaluate the portfolio frequently. Businesses should increase their strategic clock-speed to match that of the environment, with shorter planning cycles and feedback loops requiring simplified approval processes for investment and divestment decisions.

Balance exploration and exploitation. This requires having an adequate number of question marks while simultaneously maximizing the benefits of both cows and pets:

• Increase the number of question marks.

• Test question marks quickly and economically.

• Milk cows efficiently. Successful companies do not neglect the need to exploit existing sources of advantage.

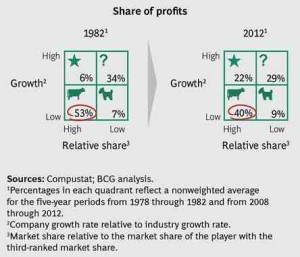

• Keep pets on a short leash. With experimentation comes failure: our analysis found that the number of pets increased by almost 50 percent in 30 years.

Select rigorously. Companies must carefully select investments as well as divestments. Successful companies leverage a wide range of data sources and develop predictive analytics to determine which question marks should be scaled up through increased investment and which pets and cows to divest proactively.

Measure and manage portfolio economics of experimentation. Understanding the experimentation level required to maintain growth is important for long-term sustainability:

• Manage the rate of experimentation.

• Drive new product and business success.

• Maintain a portfolio balance.

Increasing change certainly requires companies to adjust how they apply the matrix. But it does not undercut the power of the original concept. What Bruce Henderson wrote years ago still holds today, perhaps even more so than ever: “The need for a portfolio of businesses becomes obvious. Every company needs products in which to invest cash. Every company needs products that generate cash. And every product should eventually be a cash generator; otherwise it is worthless. Only a diversified company with a balanced portfolio can use its strengths to truly capitalize on its growth opportunities.”

by Martin Reeves, Sandy Moose, and Thijs Venema

Authors: Martin Reeves, Senior Partner & Managing Director, New York; Sandy Moose, Senior Advisor: Thijs Venema, Consultant, New York

More: BCG Classics Revisited