Having largely ignored Covid-19 as it spread across China, global financial markets reacted strongly last week when the virus spread to Europe and the Middle East, stoking fears of a global pandemic. Since then, Covid-19 risks have been priced so aggressively across various asset classes that some fear a recession in the global economy may be a foregone conclusion.

In our conversations, business leaders are asking whether the market drawdown truly signals a recession, how bad a Covid-19 recession would be, what the scenarios are for growth and recovery, and whether there will be any lasting structural impact from the unfolding crisis.

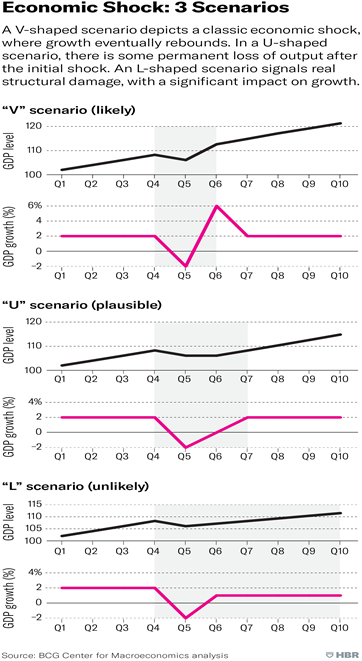

In truth, projections and indices won’t answer these questions. Hardly reliable in the calmest of times, a GDP forecast is dubious when the virus trajectory is unknowable, as are the effectiveness of containment efforts, and consumers’ and firms’ reactions. There is no single number that credibly captures or foresees Covid-19’s economic impact.

Instead, we must take a careful look at market signals across asset classes, recession and recovery patterns, as well as the history of epidemics and shocks, to glean insights into the path ahead.

What Markets are Telling Us

Last week’s brutal drawdown in global financial markets might seem to indicate that the world economy is on a path to recession. Valuations of safe assets have spiked sharply, with the term premium on long-dated U.S. government bonds falling to near record lows at negative 116 basis points — that’s how much investors are willing to pay for the safe harbor of U.S. government debt. As a result, mechanical models of recession risk have ticked higher.

Yet, a closer look reveals that a recession should not be seen as a foregone conclusion.

First, take valuations of risk assets, where the impact of Covid-19 has not been uniform. On the benign end, credit spreads have risen remarkably little, suggesting that credit markets do not yet foresee funding and financing problems. Equity valuations have conspicuously fallen from recent highs, but it should be noted that they are still elevated relative to their longer-term history. On the opposite end of the spectrum, volatility has signaled the greatest strain, intermittently putting implied next-month volatility on par with any of the major dislocations of the past 30 years, outside of the global financial crisis.

Second, while financial markets are a relevant recession indicator (not least because they can also cause them), history shows that bear markets and recessions should not be automatically conflated. In reality, the overlap is only about two out of every three U.S. bear markets — in other words, one out of every three bear markets is non-recessionary. Over the last 100 years, we counted seven such instances where bear markets did not coincide with recessions.

There is no doubt that financial markets now ascribe significant disruptive potential to Covid-19, and those risks are real. But the variations in asset valuations underline the significant uncertainty surrounding this epidemic, and history cautions us against drawing a straight line between financial market sell-offs and the real economy.

by Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak; Martin Reeves and Paul Swartz

More: https://hbr.org/2020/03/